By this time many people have heard the report on the news or read one of the numerous articles stating that a ring possibly belonging to Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect or procurator who condemned Jesus to be crucified, has been found.

The scholarly article on which the reports have been based has been published in Israel Exploration Journal 68:2 (2018). The popular article in The Times of Israel (here) includes a black and white photo of the area in the Herodium where the ring was found. I searched my photos and discovered a color picture I made of the same area in 2011. Even then some reconstructive work was underway.

Photo of the Herodium made from the garden where the ring was discovered. Photo by Ferrell Jenkins in 2011.

Our aerial photo below shows the Herodium in December, 2009. Additional excavations continue to be made on the north side of the artificial mound. The ancient fortress was hidden in the “cone” of the mound.

This aerial photo of the Herodium was made in 2009. The ring was found in the garden inside the fortress built by Herod the Great. Photo by Ferrell Jenkins.

This ring was found by Hebrew University professor Gideon Foerster during an excavation at the Herodium in 1968-9. Only now have scholars at Hebrew University been able to use modern photographic technology to read the inscription on the ring. The thin ring made of copper-alloy shows a krater with a Greek inscription around it. It reminds one of an ancient coin set in a ring. The krater was often used for mixing wine.

Views and cross section of the ring discovered at Herodium. Drawing: J. Rodman; photo: C. Amit, IAA Photographic Department.

I am not trained in things of this sort, but I immediately wondered about the spelling of the name Pilate. On the ring the Greek inscription is written as PILATO. I wondered why.

Now comes the Bible History Daily written by Robert Cargill, editor of Biblical Archaeology Review.

The ring discovered at Herodium is inscribed in Greek. And while Pilate minted several coins in Greek, he never placed his name on his coins, opting yet again to honor his benefactor, Tiberius, with the Greek inscription ΤΙΒΕΡΙΟΥ ΚΑΙϹΑΡΟϹ (Tiberiou Kaisaros; “of Tiberius Caesar”). Here, Pilate inscribes Tiberius’s name using the Greek genitive, or possessive case, to indicate that the coin was minted during the rule and under the authority of the emperor Tiberius.

Cargill wonders “why” Pilate would inscribe a ring with the name ΠΙΛΑΤΟ (PILATO) in Greek letters. He cites some reasonable info. He suggests one solution offered by Cate Bonesho, Assistant Professor of Hebrew Bible at UCLA. She says,

…ΠΙΛΑΤΟ may be a Greek transliteration of the Latin dative form of the name Pilatus.

You should be able to access Cargill’s article here. Prior to seeing his article I had already prepared a photo of the Pilate inscription discovered at Caesarea Maritima in 1961.

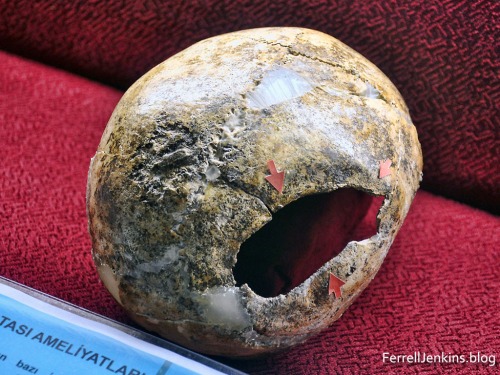

Pilate inscription discovered at Caesarea in 1961. Photo of the original in the Israel Museum. FerrellJenkins.blog.

More than seven years ago I wrote about the discovery of this stone and the meaning of the inscription here and here.

I like the suggestion made by editor Cargill, and his mention of sources of information we already have.

…the Pilate Stone, hundreds of coins, Josephus, and the Bible itself—there really was a Roman governor in Judea at the time of Jesus named Pilate.

To his list we should add Tacitus and other ancient sources. The most lengthy biblical account is in John 18:29–19:38, but Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Paul also make reference to the event.

Be careful about jumping to conclusions after hearing or reading a brief report about discoveries like this. We have waited this long and we can wait a little longer while those trained in various fields evaluate the evidence.

You must be logged in to post a comment.